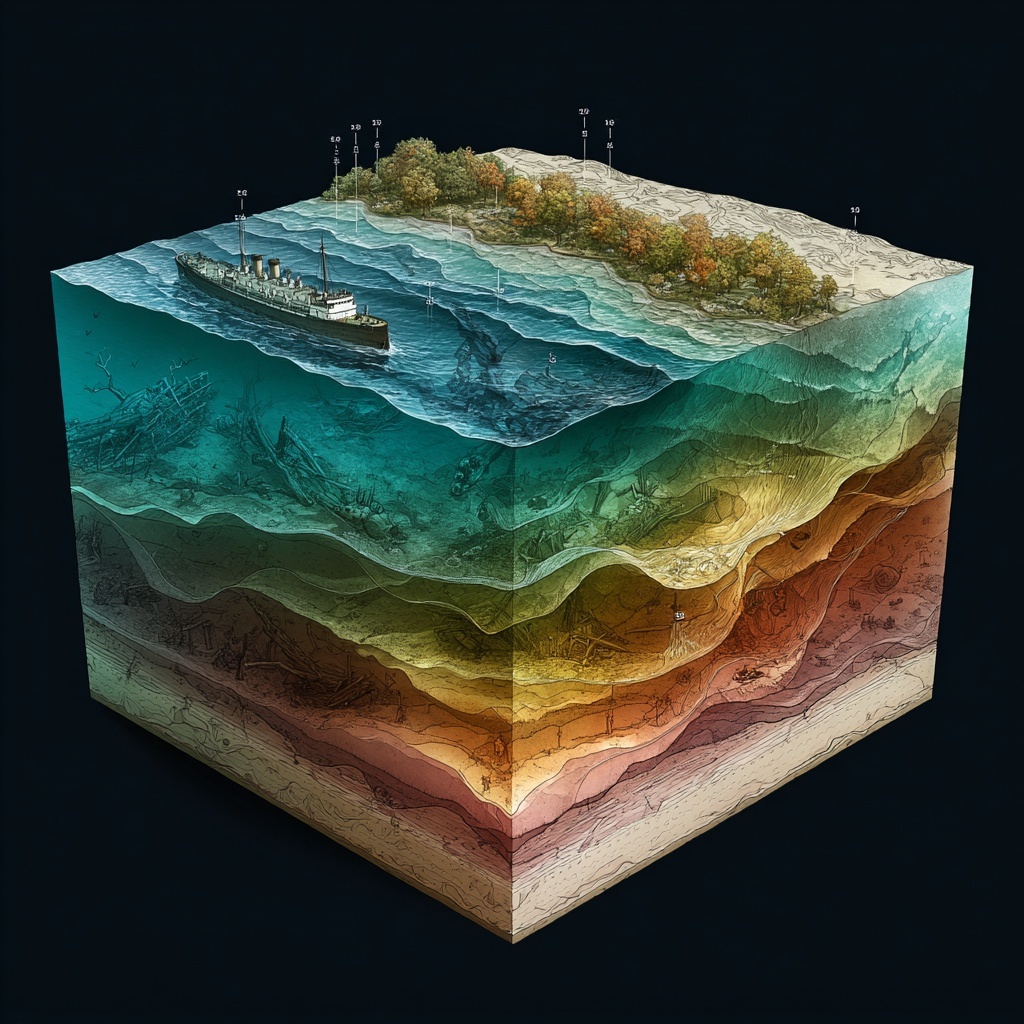

Originally appearing on his 1976 album, Summertime Dream, “The Wreck of the Edmund Fitzgerald” is a powerful ballad written and performed by folk singer Gordon Lightfoot . In 1976, the song hit No. 1 in Canada on the RPM chart, and No. 2 in the United States on the Billboard Hot 100. The lyrics are a masterpiece, but there was one specific line that always stood out to me: “The lake, it is said, never gives up her dead.” Following the singer’s death in 2023, the song reconnected with older fans and reached new generations of listeners, making it to No. 15 on Billboard’s Hot Rock and Alternative category.

Listening to it again after all these years, I was inspired to research what that line meant and if there was any truth to it. What I discovered was very illuminating: Lake Superior really doesn’t give up her dead, and the science behind it is as haunting as the song itself.

It turns out that line is not poetic license. It’s physics.

When 29 souls went down with the Edmund Fitzgerald on November 10, 1975, they stayed down. Not because of some mystical property of the Great Lakes, but because of a perfect storm of temperature, pressure, and biology that we can model mathematically.

Note: This post contains scientific discussion of decomposition and forensic pathology in the context of maritime disasters.

“The lake, it is said, never gives up her dead / When the skies of November turn gloomy”